Simple Explanation

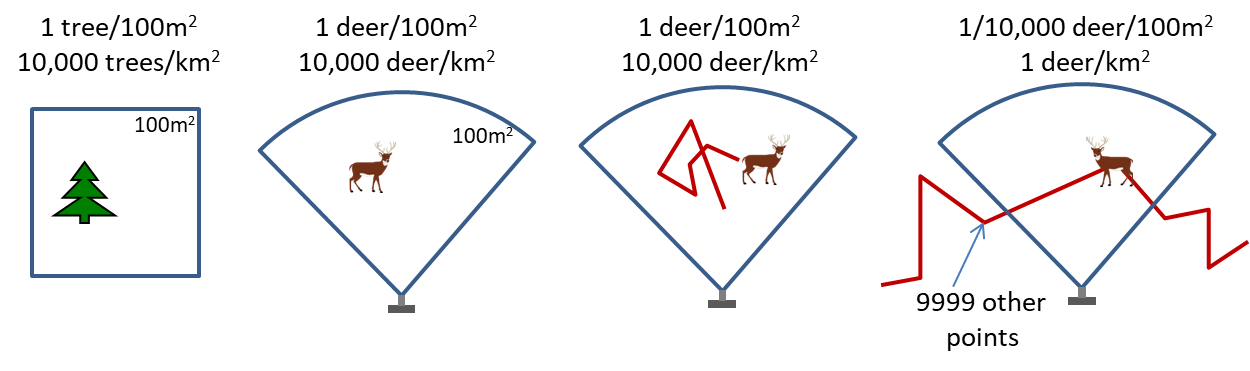

Density is the number of objects (trees, animals, etc.) per unit area. If a 100-m\(^2\) plot contains one tree, the density is 1 tree/100-m\(^2\), or 10,000 trees per km\(^2\) ( Figure @ref(fig:density)). Similarly, if a camera has a field-of-view of 100-m\(^2\) and there is always one animal in the field-of-view for the whole time that the camera is operating, the density of that species is 1 animal per 100-m\(^2\), or 10,000 animals per km\(^2\). It doesn’t matter if the animal is moving around within the field-of-view, as long as it stays in the field-of-view for the whole time. On the other hand, if that camera only has an animal in the field-of-view 1/10,000 of the time that it is operating, there is 1/10,000 animal per 100-m\(^2\), or 1 animal per km-\(^2\). If the camera has two animals together for 1/10,000 of the time, this gives 2/10,000 animals per 100-m\(^2\), or 2 animals per km-\(^2\). This is how we use cameras to calculate density.

\[Density = \frac{\sum(number~of~individuals~*~time~in~field~of~view)}{area~of~field~of~view~*~total~camera~operating~time}\]

The units are animal-seconds per area-seconds, which equates to animals per area (i.e. density).

Illustration of density for a tree quadrat and camera surveys.

For a given density of animals, this simple measure is independent of home range sizes or movement rates. If home ranges were twice as big, they would have to overlap twice as much to maintain the same density. Therefore, an individual would be in a particular camera’s field-of-view half as often (because its home range is bigger – it has more other places to be), but there would be twice as many individuals at that camera. If movement rates were twice as fast, an individual would pass by the camera twice as often, but would spend half as much time in the field-of-view (because it is moving faster). For the simple example above, there would be two visits to the camera each occupying 1/20,000 of the time the camera is operating, rather than one visit for 1/10,000 of the time. The other way of putting this is that only the total animal-time in the field-of-view matters, whether that comes from one long visit by one individual, several short visits by one individual, or several short visits each by a different individual. In all those cases, the density is the same; it is only the home range size and overlap and/or movement rates that are changing.

Two features of cameras require us to do some additional data processing to use this simple density measure:

Cameras do not survey fixed areas, unlike quadrats. The probability of an animal triggering the camera decreases with distance. We therefore have to estimate an effective detection distance (EDD) for the cameras, as is done for unlimited-distance point counts for birds or unlimited distance transect surveys. This effective distance can vary for different species, habitat types and time of year.

Cameras take a series of images at discrete intervals, rather than providing a continuous record of how long an animal is in the field-of-view. The discrete intervals need to be converted to a continuous measure to show how long the animal was in the field-of-view, accounting for the possibility that a moderately long interval between images might be from an animal present but not moving much, and therefore not triggering the camera, versus an animal that left the field-of-view and returned.

Assumptions

There are a number of strong assumptions involved in using this measure to estimate density of a species. A couple big assumptions are:

The cameras are a random or otherwise representative sample of the area. The density estimate applies to the field-of-view of the cameras. To make inferences about a larger region, the cameras need to be surveying a random or representative (e.g., systematic, systematic-random, random stratified) sample of the larger region. In particular, if cameras are intentionally placed in areas where species are more common, such as game trails, then the density estimate only applies to those places, not to a larger region.

Animals are not attracted to or repelled by the cameras (or posts used to deploy the cameras, etc). That also means that they do not spend more or less time in front of the camera because of the presence of the camera. The effect of lures or other attractants needs to be explicitly measured and accounted for.

There are additional assumptions involved in the procedures to estimate effective detection distance, including an assumption that all animals within a certain distance of the camera are detected, and in converting the discrete images into time in field-of-view. These assumptions are discussed below. Because the world is complicated, assumptions are never met perfectly. The important thing is to consider – and, ideally, design auxiliary tests to measure – is whether the violations are serious enough to impact the answer to whatever question(s) the cameras are being used to answer. In many cases, absolute density estimates may not be accurate, but the results can still serve as a useable index of relative density, if assumptions are violated about equally in whatever units are being compared (habitat types, experimental treatments, years for long-term trend, etc).

A final consideration is the sampling distribution of density estimates. Because individual cameras sample tiny areas compared to the home ranges of the species they survey, the resulting sampling distribution can be horrendous – the majority of cameras never detect the species at all (density = 0), a few cameras record the species passing by once or twice for brief periods (low densities), and a very few number of cameras record long durations as the animals forage, rest, or play in front of the camera, or revisit a favourite spot repeatedly (very high densities). Longer duration camera deployments can help smooth out some of that extreme variation, but ultimately large numbers of cameras are required for precise estimates. Appropriate questions, rigorous study designs, and modest expectations are required for camera-based studies.

Previous: Species detections